Avalanche Risk Management for the Military

When you move from recreational avalanche risk management to military operations, the core principles remain—identifying hazards, assessing likelihood/consequence, and mitigating exposure—but the context, priorities, and acceptable risk thresholds change dramatically.

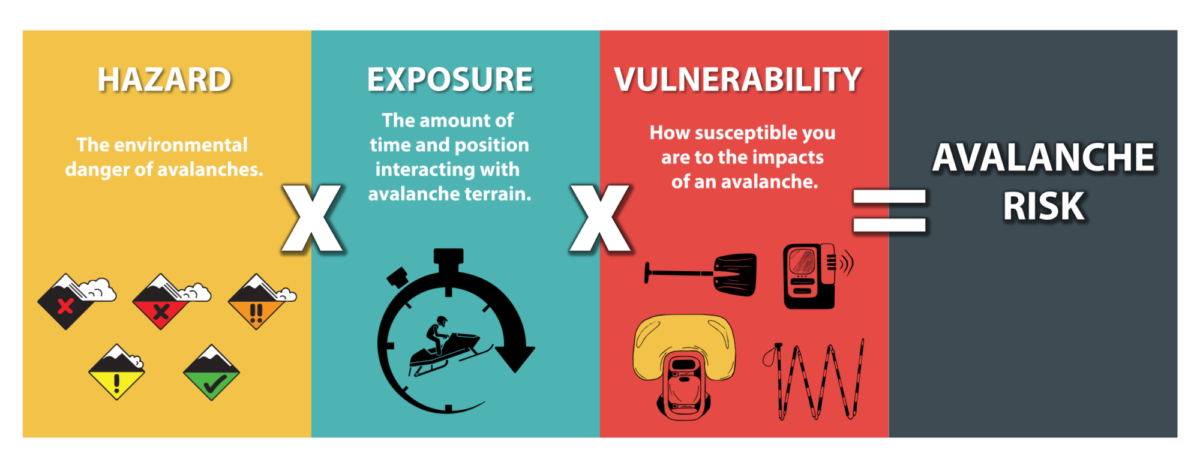

Avalanche risk in this image is a combination of the environmental avalanche danger (cannot be changed, can be mitigated), Exposure (can be changed with route selection and movement speeds), and Vulnerability (can be increased or decreased with equipment and mode of travel).

Here are some key differences:

1. Risk Tolerance and Mission Priority

Recreational: The default is “turn around if it feels too dangerous.” The primary mitigation tool is avoidance and the trip objective is secondary to safety.

Military: Mission success can require exposure to higher risk. Risk is not avoided but weighed against mission necessity. Commanders may accept risks that recreational groups would not.

2. Group Size and Movement

Recreational: Small, self-selected groups (2–6 people), often emphasizing efficient, faster, low-exposure movement.

Military: Larger groups, squad, platoon or company-sized, moving with fixed routes, equipment, and timelines. This increases exposure to avalanche terrain and complicates spacing, terrain selection, and rescue.

3. Equipment and Load

Recreational: Light skis, splitboards, or snowshoes with standard avalanche safety gear (beacon, probe, shovel).

Military: Heavier loads (40–100+ lbs), weapons, and mission-specific equipment. Avalanche gear may not be standard issue or prioritized in weight allowances. Heavier loads increase fatigue and reduce maneuverability, both of which raise avalanche exposure time without deliberate changes to movement formations and techniques.

4. Decision-Making Structure

Recreational: Collaborative decision-making; everyone ideally has a voice. Risk communication is peer-to-peer.

Military: Hierarchical decision-making. Risk assessments flow upward to commanders who may or may not be on the ground. Orders may override local avalanche concerns.

5. Rescue and Casualty Management

Recreational: Rescue assumes partners are equipped and trained to perform avalanche companion rescue (beacon, probe, shovel) immediately. External SAR is a backup.

Military: Rescue is complicated by larger groups, heavier gear, and tactical constraints. External SAR may be unavailable, so units often must be self-sufficient. Evacuation timelines coulde be shorter or longer depending on the operational context. Often, life saving medical support is immediately available within the unit.

6. Training and Expertise

Recreational: Increasingly standardized avalanche education with emphasis on forecasting and decision frameworks.

Military: Training varies widely. Some specialized mountain/winter units get professional avalanche education, but many soldiers operating in snow-covered terrain have limited to zero avalanche-specific training. Human factors (inexperience, fatigue, pressure to follow orders) are amplified.

7. Operational Constraints

Recreational: Choice of objective, timing, and terrain is flexible. Groups can delay, reroute, or bail entirely.

Military: Movement is often dictated by mission windows, logistics, or concealment. Units may need to move at night, in storms, or through high-risk terrain despite elevated avalanche hazards.

Here are some definitions for the terms shown above.

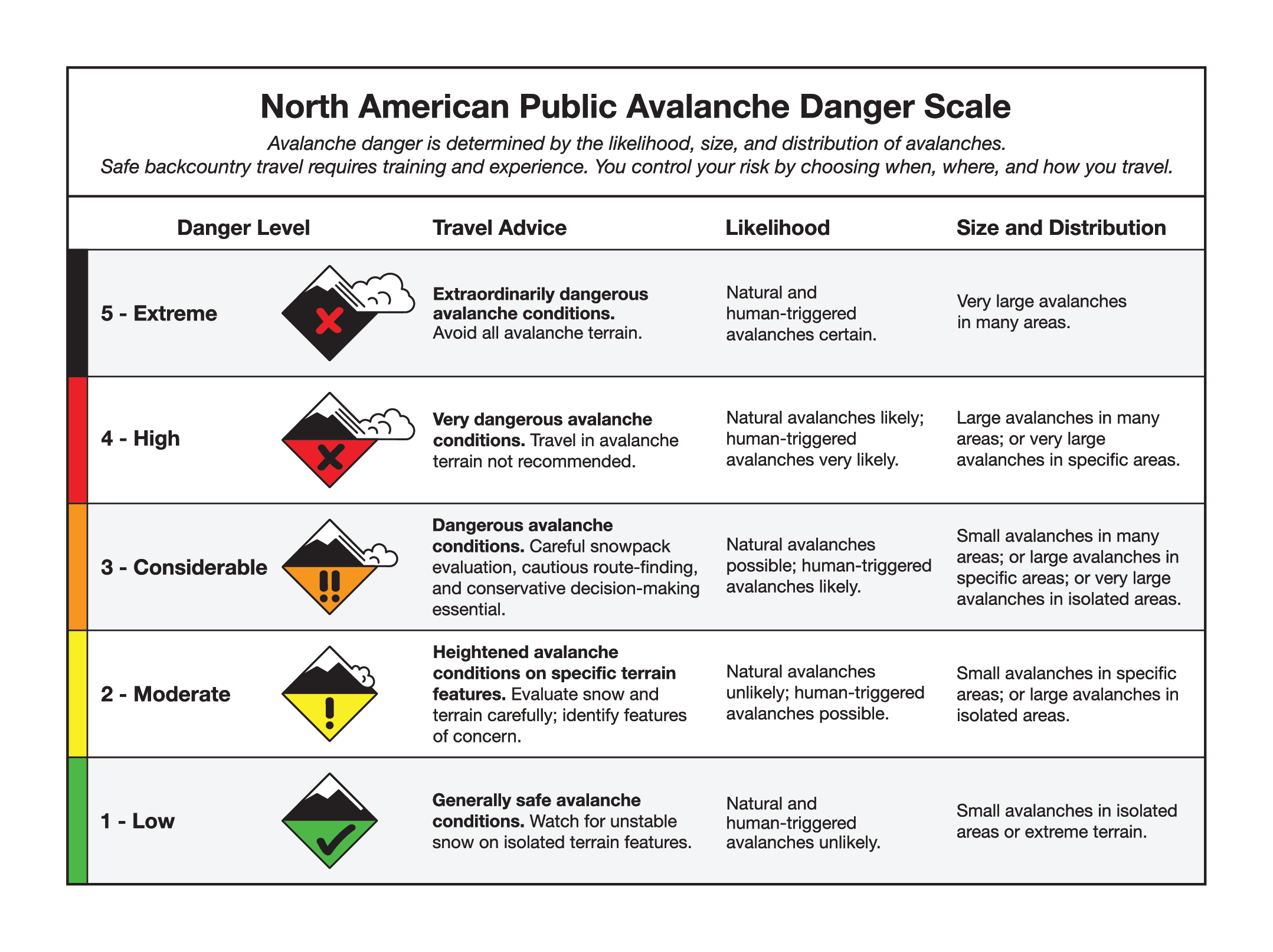

Unlikely: Your odds of triggering an avalanche are very low but not impossible. Your day should go uneventfully without triggering or encountering an avalanche.

Possible: There are a handful of problematic steep slopes where you could encounter an avalanche today. When avalanches are “possible”, you will return home without an avalanche encounter more often than triggering an avalanche, but both outcomes can be expected from time to time.

Likely: The odds are favorable that you will encounter or trigger an avalanche today. You should trigger several of the steep slopes that you cross and/or some terrain will avalanche naturally.

Very Likely: Most of the steep terrain that you travel on will avalanche, and you’ll encounter numerous natural avalanches.

Almost Certain: You will trigger an avalanche on almost all of the steep terrain that you cross–if it hasn’t already released naturally–throughout the day. If you look around, you’ll witness a widespread avalanche cycle.

Isolated

Avalanches are expected only in a few, very specific locations. These are uncommon problem spots (e.g., one particular slope aspect, an unusual terrain trap). Travel is generally safer if those areas are avoided.Specific

Avalanches are expected in certain terrain features, but not everywhere. The problem is tied to particular slope aspects, elevations, or terrain types (e.g., north-facing slopes near treeline). Route-finding and terrain selection are essential to avoid these features.Widespread

Avalanches are possible on many slopes across multiple aspects and elevations. The problem is broadly distributed, making safe route options much more limited. This often corresponds with higher avalanche danger levels and requires very conservative decision-making.✅ These terms are layered on top of likelihood and consequence in the risk framework, giving forecasters and users a three-dimensional picture:

Likelihood (chance of triggering)

Consequence (size/severity)

Distribution (how broadly the problem exists across terrain)

✅ Summary:

Recreational avalanche management prioritizes safety and voluntary risk acceptance, while military avalanche risk management integrates hazard analysis into a mission-driven context where higher risk may be deliberately accepted. The key shift is from a safety-first model to a mission-first model with managed risk, requiring adapted training, equipment, and decision frameworks to avoid preventable mass-casualty events.